Contracting the workforce locally not only lowered the costs of the programme, but also generated greater community empowerment and sustainability of the workforce

Case study

Sustainable urban development in El Salvador

SDGs ADDRESSED

This case study is based on lessons from the joint programme, Urban and Productive Integrated Sustainable Settlements El Salvador

Read more

Chapters

Project Partners

1. SUMMARY

The intervention centred on designing and implementing a model of productive and sustainable urban settlements in El Salvador. The objective was to transform the poor conditions and exclusion of those who live in the slums while optimizing the value chain within the construction of social housing, and having an impact on public policies. In order to do this, 884 urban slums in the metropolitan area of San Salvador and the Apopa and Santa Tecla districts were converted into productive and sustainable urban settlements. The programme coincided with The Republic of El Salvador’s five-year development plan, the settlement policy being one of the strategic lines of said plan.

The programme helped to implement the Law on the Legalization of Land Ownership and Development Banking – the most important regulation of the land ownership1 legalization law in the history of the country – in the first phase of legalizing urbanization and land that included 60,000 homes. For the first time, a system of guarantees for housing credit from the Salvadorian Guarantee Fund was implemented, operated by the Development Bank of El Salvador.

On the practical side, the School of Construction Micro-Entrepreneurs was created, founded as a programme of technical training at the University of El Salvador, strengthening connections in the construction value chain.

This case study attempts to highlight the lessons learned, results and practical examples to strengthen the knowledge of development programmes which promote architecture and the design of housing as tools for alleviating the poverty and marginalization that some populations live in.

1 Land ownership: Inheritance, haciendas, land or possession of a dwelling.

El Salvador’s housing deficit stands at around 3600,000 houses / SDGF

2. THE SITUATION

The Republic of El Salvador has a population of 6.2 million, of which more than 63 per cent are under the age of 30. The country had a civil war in the 1980s, caused, among other things, by economic inequality and the lack of redistributive public policies.

El Salvador’s housing deficit stands at around 360,000 houses . This, combined with the precarious nature of many of the urban settlements and overcrowded conditions, not only impacts the inhabitants’ quality of life, but it is also a source of conflict which reduces the potential and economic development opportunities of the population. Before the intervention, the State did not use mechanisms to help the situation. In the absence of property taxation, they openly supported the concentration of property, the availability of uncultivated land, and speculation on its value.

In addition, until 2012 there was a lack of legal planning permission and more than 30 per cent of the country’s urban dwellings were built with no permission and without deeds of ownership. The private sector was connected with the construction value chain, but within unregulated frameworks and with a shortage of public-private alliances.

From this perspective, the challenge of intervention focused on the creation of a model of productive, sustainable urban settlements which provided inhabitants with the conditions and opportunities necessary in order to lift themselves out of poverty. This social housing would improve living conditions and access to proper housing.

At the beginning of the intervention, when the baselines were being established with respect to precarious dwellings, it became clear that the dwellings were excluded from the social, economic and urban structures of the areas around them. The prioritized settlements were not produced for the community, but were sleeping areas for the poorly qualified and badly paid workforce, which worked outside of the municipality and who did most of their purchases outside of the settlements. In turn, it became evident that school admissions and levels of study among the women were low, and that furthermore a gender strategy for the intervention should prioritize a younger person’s standpoint.

The assessment showed that the women’s productive activity was found to take place in the close surroundings of the settlement. For this reason, from the start, the programme invested in training and female entrepreneurship in order to develop the local economy.

Finally, the infrastructure component had to consider the design of secure spaces that could guarantee equal use and enjoyment of the city by women. Special attention was paid to the participation, product development and construction of buildings that guaranteed spaces for communal living for young people during the implementation of the programme.

1 The income per capita is $3,590 and the poverty rate is 34.5 per cent

2 According to Government data from 2010

3. STRATEGY

The programme developed three principal strategies, linked to the local authorities and communities in the formalization of the following activities:

- Developing a model of productive, sustainable urban living spaces in order to improve the living conditions of those most in need, by offering new homes and improved habitations financed by the public and private sectors.

- Strengthening the construction industry’s value chain of social housing by offering accessible products and services for those with few resources, thus encouraging the formation and participation of small and medium-sized businesses.

- Encouraging the local economic development of areas around the settlements, with emphasis on young people and women.

4. RESULTS AND IMPACT

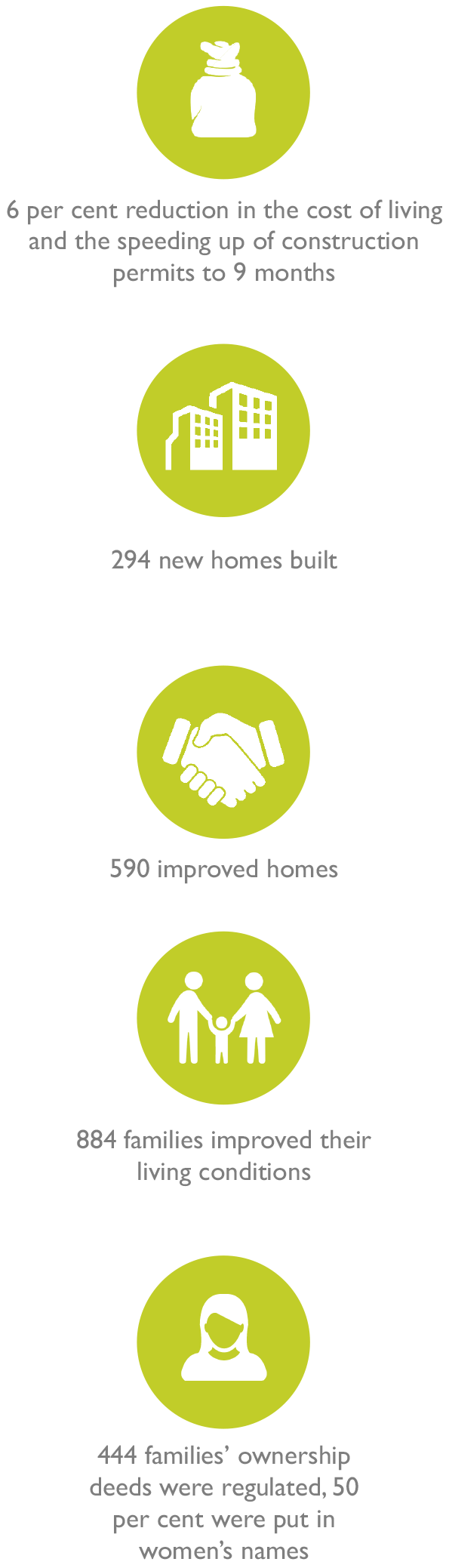

The intervention helped to strengthen the public housing sector, by presenting two design proposals and a new regulatory framework to the public administration, creating two models of productive, urban sustainable settlements (new and improved living spaces). Among other characteristics, this model reduced the cost of living by 6 per cent and reduced waiting time for planning permission to 9 months. Once the model had been developed, two urban settlements in which to implement it were selected in the metropolitan area of San Salvador. This improved the living conditions of 884 families through the creation of 294 new houses and the refurbishment of 590 homes. The legal status and ownership deeds of 444 families were regulated, of which 50 per cent were put in the name of women.

The precarious nature of urban settlements and overcrowded conditions impact the inhabitants’ quality of life and economic opportunities

The policies and procedures surrounding urbanization and housing construction were revised, rationalized and implemented. The programme helped to draft seven bills – Land Development Ordinance; Subdivision of Land; the Development Bank; Social Housing; Condominium Building; Simplification of Construction Procedures; Updates to Urbanism Laws; and Construction - of which three were approved by the Assembly during the project: Land Development Ordinance; the Development Bank; and Subdivision of Land Laws.

An original financial mechanism was pioneered, by working on the design, structure and implementation of the National Programme of Social Housing Guarantees, and by promoting the Memorandum of Understanding with the Central Bank of Reserva, the Superintendent of the Financial System, the Multi-sector Investment Bank and the Development bank of El Salvador. Furthermore, financial equality was promoted through the Mobile Financial Bank, which meant that 50 per cent of the approved credit would be given to women.

In addition, new production and negotiating practices were developed in order to reinforce the inclusive characteristics of the production line. The programme prepared a diagnostic of the value chain and set up a public-private board called Alianza for the Social Interest Dwellings, dedicated to overcoming obstacles and guaranteeing diversity in the production line. In parallel, ten small and medium-sized businesses qualified for the provision of goods and services from the large businesses in the construction industry. In addition, apprenticeship and job training programmes for 15 workers were organized. These programmes were the beginning of the first school for bricklayers.

In order to promote local economic development, four productive activities were implemented: 1) The Gourmet Apple (La Manzana Gourmet), in Santa Tecla; 2) The Megastore (La Megatienda), in Apopa; 3) The Peri-urban Agricultural Project (el Proyecto de Agricultura Periurbana), in Apopa; and 4) The Recreation and Culture Project (el Proyecto de Recreación y Cultura), in Apopa. These activities involved 364 families (and had 80 per cent female participation) and 111 service micro-enterprises in Santa Tecla, and two companies of construction micro-enterprises in Apopa and Santa Tecla. 100 families were made aware of topics to do with sustainable local economic development.

To forge alliances with the private sector and to promote an exchange of ideas, a list of experts was created which started with 130 businesses and 19 thematic windows. This initiative caused much expectation, and various groups actively participated in the exchange of good practices and knowledge. Consequently, five collaboration agreements between communal associations from the selected settlements were agreed upon.

5. CHALLENGES

- Although the participation of different United Nations agencies proved to be a very efficient multi-dimensional method in terms of getting results, the participating agencies’ different administrative systems proved to be incompatible, which caused communication problems. This brought to light the need to design an administrative plan together in order to define shared channels and procedures with a view to reducing costs and proceeding in a more efficient manner. From the start, the programmes should ensure that they share a clearly-defined communication strategy which will allow them to transmit an understanding of the same to all participants, beyond specific promotional events.

- The rotation of personnel in medium- or long-duration initiatives – those longer than two years – creates information gaps and long periods of adaptation, which can only be corrected with permanent information strategies and the maintenance of an active institutional memory. Systems to avoid the loss of human resources and expertise created during the programme must be developed, in order to guarantee sustainability, alongside the organizational procedures that have been initiated and good practice.

6. LESSONS LEARNED

- The programme is a successful point of reference of the abilities and the impact of the United Nations when its agencies work in a coordinated and multidimensional manner. Each one brought its own knowledge and experience. Of course, in order for the intervention to be successful, it is very important that clear roles are assigned and agreements established about communal objectives, followed by mutual learning by the connected agencies and institutes. The role of the agencies and institutions that lead the programmes should be that of facilitators, not protagonists, in order to maintain a harmonious and productive working relationship with the participants.

- It is important to promote active participation and dialogue between the beneficiaries when the strategies, methodologies and processes are being planned, in order to foster acceptance and adoption of the projects. It is precisely this vital element of adoption which will lead to sustainable actions. Nothing should be “imposed”, and the leadership skills of the local participants should be promoted, as they are the ones who will drive the project forward. One of the biggest successes of the programme was accomplishing direct cooperation with the community, without intermediaries, which allowed the programme to home in on their needs.

- Building infrastructures in the communities generated labour opportunities. The programmes should not deplete their actions, but rather they should promote the idea that women and men could benefit equally from the employment opportunities generated. In addition, contracting a local workforce not only lowers the costs of the programme, but also generates greater community empowerment and sustainability of the workforce.

- During the implementation of the activities it is good to incorporate informal reflection spaces so that political groups and different people involved in the projects can discuss their neutrality and legitimacy in the presence of the UN.

- In order to ensure better adoption and sustainability, it is important that the development programmes adhere to national strategies or established public policies that are already in use. For this, it is important to have a method and policy agreement within the government, prior to the presentation of initiatives to the Congress. A success of the programme was its materialization beyond the petition.

7. SUSTAINABILITY AND POTENTIAL FOR REPLICATION

The sustainable urban living programme in El Salvador can be a reference for the rest of the projects going on in the country, but also for other regions, insomuch as it achieved impact in all levels of the intervention: from the community to national public policies. Furthermore, this intervention is especially relevant for community empowerment and participation. It involved civil organizations and groups of women who actively contributed to the process. It is precisely this local adoption that is a vital issue for the sustainability of the project. This significantly contributed to decision-making, a process in which the communities were not considered simply as beneficiaries, but rather as collaborators and managers of their own development. The communities learned techniques and gained knowledge that will last through time, strengthened local governance and said communities established direct dialogue channels with local authorities to exert their rights and receive institutional support.

On a national level there are great prospects for sustainability thanks to the government’s commitment, the investment made with resources from the national budget, and the creation of laws and documents that were unprecedented in the country. They not only helped to overcome bottlenecks in the construction of the settlements, but also allowed a framework of far-reaching institutionalism. Because of this, the programme received special recognition from the Legislative Assembly for its contribution to the country and its regulatory frameworks, such as the adoption of the Land Legalization Laws and the Development Bank; the regulation of the Mobile Bank and Financial inclusion; and the adoption of the Land Development Ordinance.

At a local level, a high appropriation rate by the local town halls was registered, who demonstrated their desire to continue, and even replicate, the model of productive and sustainable settlements that was created. In addition, during the implementation there was continuous support from local governments, which manifested itself in financial, technical and human resources which helped the activities.

Building infrastructures in the communities generated labour opportunities / SDGF