In the municipalities prioritized by the programme, the following practices were found: inadequate breastfeeding and supplementary feeding, poor hygiene and childcare practices, and poor diet (monotonous, low in fruits, vegetables, dairy products, meats and fats; and high in plantains)

Case study

Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities in the Chocó department promote their food security and nutrition in Colombia

SDGs ADDRESSED

This case study is based on lessons from the joint programme, Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities in the Chocó department promote their food security and nutrition

Read more

Chapters

Project Partners

1. SUMMARY

The intervention aimed to improve the food security and nutrition of the selected indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities in the Department of Chocó, Colombia. Special emphasis was placed on raising the visibility of child malnutrition- especially for children up to the age of five, with an emphasis on children under the age of two - and to recognize its association with food, health, hygiene and care factors. To that effect, the prevention strategy titled “Seres de cuidado” [Persons of Care] was developed, which included 13 key health practices to prevent child malnutrition. Pregnant and breastfeeding women not only benefited from this training but also actively participated in and promoted respect for and the protection of social, cultural and economic rights, especially the right to food.

Food packages were provided on a monthly basis to the families of children at risk of malnutrition

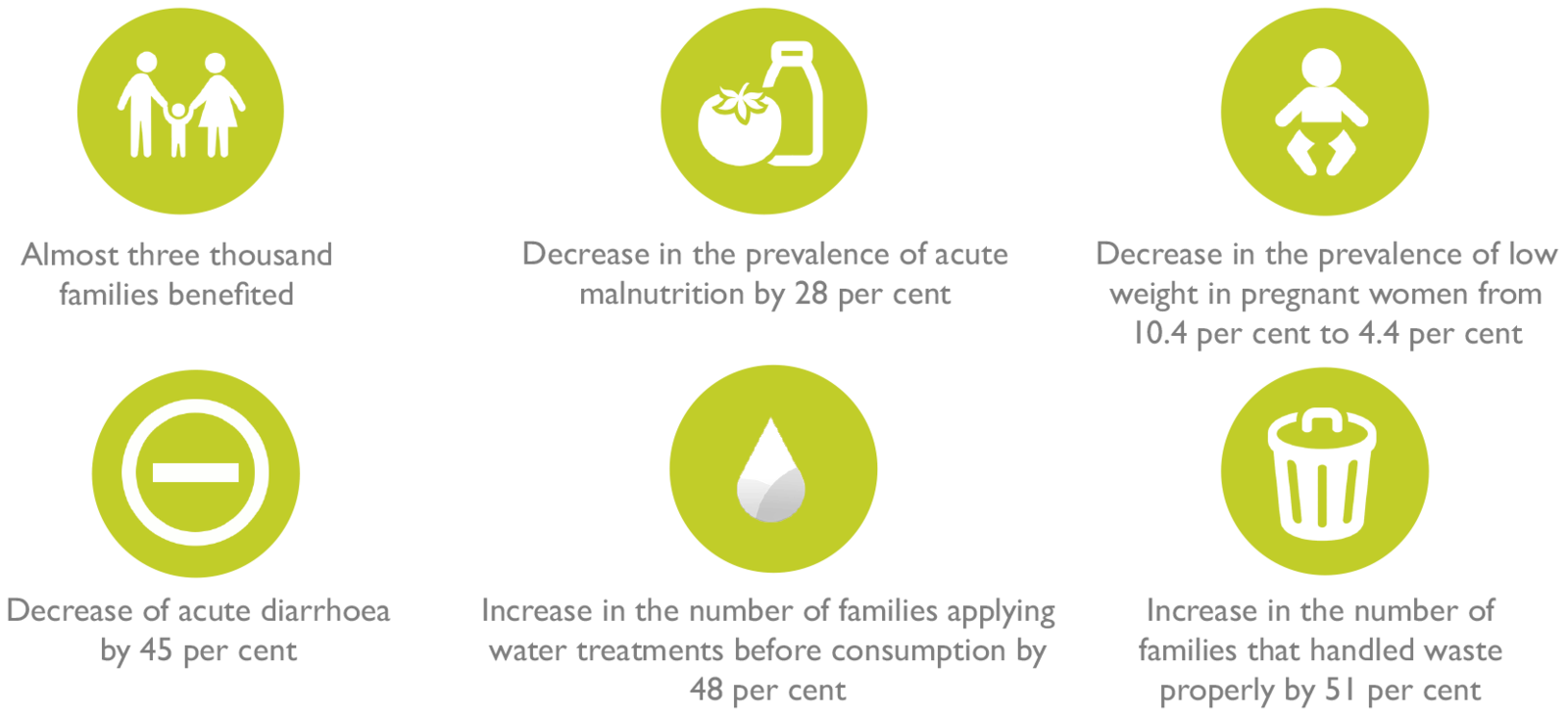

The programme was developed in 58 communities 25 Afro-Colombian and 33 indigenous - from 9 municipalities - Quibdó, El Carmen de Atrato, Río Quito, Nóvita, Sipí, Tadó, Istmina, Medio San Juan and Litoral de San Juan -, decreasing the prevalence of acute malnutrition by 28 per cent and theprevalence of diarrhoea in children by 45 per cent. In total, 2,943 families benefited.

The aim of this case study is to showcase the learning, results and practical examples of this experience to reinforce knowledge about food security and nutritional programmes.

2. THE SITUATION

The Department of Chocó is located in the northwest region of the country. It has an area of 46,530 km2 and is the only Colombian department with a coast on the Pacific Ocean. Chocó has a population of 454,030 inhabitants, 70 per cent of whom predominantly come from rural municipalities. It is considered as one the richest regions in the world for natural resources. Moreover, the presence of Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities bring important cultural wealth to this region, since these people have conserved their languages and customs. However, Chocó’s economy is fragile; it depends on mining, logging, fishing, agriculture and livestock. The mining industry makes the largest contribution to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), with a share of 30 per cent. Even so, the mining boom in Chocó is also associated with conditions of poverty. This activity involves high environmental and social risks and risks the exacerbation of violence over the control of resources.

The Chocó region has more poverty and lower quality of life levels than Colombia’s national averages. Colombia’s quality of life index is at 79 per cent, while in Chocó it is at 58 per cent. Life expectancy in Colombia is 70.3 years, while in Chocó it is only 58.3 years. The mortality rate among children under the age of five is also higher than Colombia’s national average. In 2005, children under the age of five (in the Chocó region) were malnourished in 60 per cent of the cases, compared to Colombia’s national average of 33 per cent. Of that 60 per cent, 77 per cent suffered from chronic malnutrition and 45 per cent from severe chronic malnutrition, compared to the national level of 2 per cent. In addition, in the municipalities prioritized by the programme, the following practices were found: inadequate breastfeeding and supplementary feeding, poor hygiene and childcare practices, and poor diet (monotonous, low in fruits, vegetables, dairy products, meats and fats; and high in plantains). Moreover, it must be taken into account that 29 per cent of girls between the ages of 15 and 19 in Chocó are either mothers or pregnant with their first child. The maternal mortality rate in Chocó is triple that of Colombia’s national rate. Likewise, gender-based violence in Chocó is at 88.3 per cent, exceeding by far Colombia’s already high national average (55 per cent).

At the same time, there is a close link between food insecurity and armed conflict. According to the “Evaluation of Food and Nutrition Security in Vulnerable Populations in Colombia (2011)”, the presence of illegal armed groups and anti-personnel mines restricts the population’s ability to access their food sources: markets, hunting, fruit picking and fishing.

3. STRATEGY

The programme was developed in 58 communities (25 Afro-Colombian and 33 indigenous) from 9 municipalities: Quibdó, El Carmen de Atrato, Río Quito, Nóvita, Sipí, Tadó, Istmina, Medio San Juan and Litoral de San Juan. Initially, a review of the existing legal framework on food security was carried out, taking into account (at all times) the cultural integrity of indigenous peoples and ethnic groups. In this phase 69 representatives of the indigenous ethnic groups and 36 legal representatives from the Afro-Colombian community councils participated. After this review, the communities carried out a process of adjustments and understanding of the concepts of food security, nutrition and malnutrition.

The programme revolved around two main areas:

- Community strategy for nutritional recovery of malnourished children through capacity building to prevent, detect and refer cases of malnutrition. The objective was to strengthen the inpatient care model that had been implemented in Chocó since 2007. This model led to high costs, low coverage in care - especially in rural areas - and a high workload for professionals in nutritional recovery centres. Knowledge and tools were provided to detect malnutrition and infectious diseases in children, such as the use of a three-colour tape to measure arm circumference, the detection of physical signs that are characteristic of malnourished children, and the danger signs of prevalent childhood diseases: acute diarrhoeal disease (ADD) and acute respiratory infection (ARI). Food packages were provided on a monthly basis to the families of children at risk of acute or general malnutrition. This was complemented by other initiatives, such as the encouragement of breastfeeding, education on health, hygiene and food habits, monitoring the nutritional status of children and pregnant women, vaccinations, literacy training for mothers, and improving the quality of water and basic sanitation

- The “Seres de cuidado” strategy is a conceptual, technical and methodological proposal that integrated the Institutions Friends of Women and Children (MISEI) strategies, creating a guide of 13 good practices. The methodology used in “Seres de cuidado” was characterized by community and institutional participation, based on actively listening to the different stakeholders involved in improving health and nutrition in Chocó. The strategy was designed so that caregivers, under the primary health care model implemented and strengthened 13 key community-level practices that would contribute to reducing morbidity and mortality from malnutrition, as well as associated diseases in children under the age of five.

4. RESULTS AND IMPACT

The main achievements of the intervention are as follows:

- Strengthening capacities to identify malnourished children proved to be effective. The use of the knowledge and tools provided helped to detect 35 per cent of the total malnourished children. 169 volunteers participated inindicator of prevalence of underweight for age experienced a considerable decrease in the percentage of children who were tended to under the age of this process.

- The six, which went from 15.3 per cent to 10.7 per cent. The programme reduced the prevalence of acute malnutrition by 28 per cent. When comparing nutrition indicators with Colombia’s national and departmental levels, it can be concluded that, thanks to the intervention, in the areas where the programme was implemented, general malnutrition was 0.7 percentage points below the prevalence reported by Colombia’s National Nutrition Survey (ENSIN 2010). In addition, the prevalence of pregnant women with low weight decreased from 10.4 per cent to 4.4 per cent.

- The use of drinking water for direct consumption and food preparation is considered a primary factor in nutrition. The evaluation identified an increase in the consumption of safe water by the families, reflecting in turn a decrease in the cases of diarrhoea in children. At the beginning of the intervention, only 27.9 per cent of the families used some type of water treatment; 9 months later, this indicator rose to 54.6 per cent. In the last evaluation period, 76.6 per cent of families applied some type of treatment to their drinking water, which meant a total increase of 48.7 per cent.

- The prevalence of acute diarrhoea in children in the selected communities was reduced by 45 per cent. This prevalence of acute diarrhoeal disease in children under the age of 5 is 2.4 percentage points below Colombia’s incidence rate of 13 per cent. Strategies for reducing diarrhoea decrease the risk of death from dehydration or excessive fluid loss during illness.

- The number of families with adequate garbage and waste management increased by 51 per cent. At the beginning of the evaluation, only 11.9 per cent of the families carried out adequate waste disposal practices. The percentage recorded in the final evaluation was 62.5 per cent. This is another key indicator of malnutrition in children, since it favours the reduction of rodents and pests that affect the population’s environment and health.

5. CHALLENGES

- Creating a joint administrative agenda that defines shared channels and procedures to reduce costs and to manage more efficiently. It must be ensured that, from the outset, the programmes have a clearly defined communication strategy between stakeholders, which allows the beneficiaries to be given an understanding beyond specific promotional events. It is also necessary to provide the programme’s national coordination with effective mechanisms to enforce the commitments made by each of the stakeholders to ensure the programme’s success.

- Creating action plans that take into account the communities’ time management, especially indigenous communities, and coordinate the commencement of different strategies. The time elapsed between closing the agreement and having it signed affected the processes’ development. The disbursement of resources in annual cycles affects the continuity of actions and the achievement of results.

- Policy makers and technicians should become sensitised on the importance of addressing food security and nutrition in an intersectoral and integrated way. Educating and raising awareness about the need for the intervention and its methodology is vital in engaging stakeholders.

- The population’s habits, practices, and cultural customs require a prolonged process towards a change in behaviour aimed at better health and nutrition.

- Establishing training processes such as the Diploma in Food Security and Nutrition at the beginning of the intervention in order to facilitate an understanding of the proposal and initiate a dialogue between men and women leaders. Encouraging the exchange of experiences in the training context.

- Training community leaders in workshops and diplomas with the aim of strengthening their capacities for applying the proposal in their communities, and its incorporation into public policies.

- Strengthening the role of departmental and local institutions to promote the sustainability of the implemented strategies and their impacts over time. It is necessary that these strategies be put together as public policies of a binding nature, as is the case with Colombia’s municipal development plans.

- It is difficult to ensure the transfer and permanence of facilitation teams in order to interact with local stakeholders, especially in areas difficult to access.

- Staff turnover in medium and long-term initiatives (over two years) generates information voids and long adaptation processes, which can only be shortened with permanent information strategies and the maintenance of an up-to-date institutional record. Mechanisms must be designed to avoid the loss of human resources and technicians trained during the programme’s process to ensure the sustainability of organised initiatives and good practices.

The “Seres de cuidado” strategy was characterized by community and institutional participation

6. LESSONS LEARNED

- The programme constitutes a successful example of the capacity and impact of the UN when its agencies work in a coordinated multidimensional way. Each agency contributed its own knowledge and experience. However, in order for the intervention to be successful it is very important for the roles of the different agencies to be made clear and for agreements to be established around the common objectives, thus providing mutual learning for the agencies and linked institutions.

- The issue of representation within the community is always problematic. The term "community" is often used as if it represented a homogeneous, clear and definite structure. However, it hides a range of particular interests in terms of economic position, ethnic status, gender equality and age. It is essential to take these complexities into account when approaching the communities and not to start out from erroneous hypotheses.

- In most countries, on the subject of public policies, efforts on nutrition and food security are guided by vertical plans that address the problem from the exclusive perspective of each theme such as: health, agriculture, education and children. Lack of a horizontal public policy on nutrition leads to problems of coherence, interaction and coordination, resulting in a duplication of efforts and inefficient use of resources. It was precisely the interdisciplinary work and active listening between different stakeholders that allowed the implementation of a strategy like "Seres de cuidado".

- Education is the key strategy that allows stakeholders and beneficiaries to understand the importance, impact and benefits of the programmes, as well as relevant concepts such as food security and malnutrition, adapting them to their own context. It is important to establish a process of continuous education in development interventions.

- Regular support for families and communities is essential to improving living conditions and adopting good health, food, hygiene and child care practices.

- In order to ensure greater ownership and sustainability, it is important for development programmes to align with existing national strategies or established public policies.

- All development experience must take a bottom-up approach, where the development of different interventions is consulted, validated and implemented with the community. In order to improve impact, ownership and sustainability levels, it is necessary to prioritize the local level, linking communities, local partners and regional advisers in the processes of planning, monitoring and evaluation of activities.

- The remote location of many communities means that there are not many professionals prepared to run the risk of sharing experiences with these groups and to train them. Therefore, when it comes to indigenous communities, it is absolutely necessary to strengthen local capacities to carry out these activities and ensure their success is sustainable over time.

In 2005, children under the age of five in the Chocó region were malnourished in 60 per cent of the cases

7. SUSTAINABILITY AND POTENTIAL FOR REPLICATION

The promoted practices can be a reference for the rest of development projects that are carried out in Colombia, and also for other countries. This intervention is especially relevant for community participation and empowerment, mainly of indigenous and Afro-Colombian groups. Civil organizations, indigenous representatives and women's groups were involved. They actively contributed to the process.

In decision-making, communities were not considered merely as beneficiaries but also as collaborators and agents of their own development. This serves to generate, little by little, changes from the base of the society that will later move up to public institutions. This was the case of some councils and community councils that, after the intervention, began to incorporate some of the practices promoted by the programme. This ownership is precisely what is needed for the sustainability of the actions.