Young men and women who were likely to migrate, or those who were just returning, boosted their ability to properly incorporate themselves into the labour market. National and local institutional frameworks were strengthened to promote proper employment to the young people likely to migrate and returnees

Case study

Generating employment opportunities for young people in Honduras

SDGs ADDRESSED

This case study is based on lessons from the joint programme, Human development for youth: overcoming the challenges of migration through employment

Read more

Chapters

Project Partners

1. SUMMARY

The goal of the intervention was to generate opportunities for decent employment and entrepreneurship, and to stop the young people with high migration potential between 15 and 19 years old, and those in vulnerable situations, from leaving the country. The programme focused on 22 municipalities in the regions of La Paz, Comayagua and Intibucá, and was structured around three fundamental activities:

- Increasing young people’s ability to properly place themselves in the labour market.

- Strengthening the national and local institutional frameworks to promote suitable work.

- Strengthening the leadership, roots and identity of young people and including them in the creation of a local development vision shared by the community.

The intervention contributed to generating suitable employment opportunities for young people through skills training programmes, as well as financial and technical assistance in order to start their businesses. At the same time, awareness activities about gender, employment and the prevention of violence were held.

This case study aims to expose the lessons learned, results and practical examples from the intervention, with the intention of reinforcing knowledge about the interventions in the fields of employment and youth, and also the approach to these questions from a gender perspective.

The intervention aimed to create opportunities to discourage emigration among young people vulnerable

2. THE SITUATION

In Honduras, poverty affects 72 per cent of the population, the situation being especially serious in rural areas and, in particular, in the south-west region. More than half of the population (around 4 million people) live in conditions of extreme poverty, while the rest of the poor population (more than 1.5 million people) are able to buy food but no other basic necessities for education, health or living1.

Honduras is characterized by a predominantly young population. The young people under 29 constitute 67 per cent of the population. Youth unemployment is an urgent problem snce more than half of those unemployed are under 24, while 50 per cent of working young people are in precarious employment where their salary is under the minimum wage, without social protection, with long working days and with little or no union representation. This is the case particularly for women, whose participation in the active population is less than that of men and, in addition, suffer from obvious salary inequality: the average salary for a woman is 5,828 American dollars, compared with the average 9,835 dollars that a man earns2.

In the last two decades, Honduras has experienced a considerable amount of migration abroad. In 2012, 57 per cent of Honduran emigrants were men, and 43 per cent women. Of course, although there are only a few women that emigrate, several studies indicate that they experience more dangers when traveling, including sexual trafficking. In homes in which the partner has migrated, the woman has to assume both the reproductive and productive tasks, which increase their workload.

3. STRATEGY

The programme took place in three regions: La Paz, Intibucá, and Comayagua, two of which (La Paz and Intibucá) are rural, with predominant indigenous Lenca populations. The programme worked with vulnerable young people with few skills and who did not meet the minimum requirements in order to obtain credit from financial institutions. The following strategies were developed:

- Promotional and employability strategies focused on insertion into the labour market, which comprised the following actions: 1) analysis of training institutions for employability; 2) the creation of territorial committees for youth employment; 3) the creation of Multi-Service Offices (OMS) for the promotion of employability and entrepreneurship at a municipal level; 4) skills training for company employment; 5) agreements with local businesses and internships for trained young people.

- Business development strategy. Traditional banks consider the younger population to be a high-risk group, especially women and young people from rural areas, given that they do not have assets and are likely to emigrate. Consequently, this group finds it difficult to access financial services. To combat this reality, a strategy focused on self-employment was implemented, using the following processes: 1) analysis of productive lines with great potential; 2) training in business management skills; 3) financial support through a credit fund controlled by co-operatives and rural funds, and a “seed capital” fund controlled through municipal offices; 4) technical assistance to improve production processes and marketing, among others.

- Gender awareness programme which aimed to raise awareness for the participation of young women in the labour market.

The Multi-Service Offices (OMS) were the nucleus of the intervention as they were in charge of coordinating all of the job placements and training, and putting them in contact with young people. These offices maintained a database with the young people’s CVs that was linked to the job offer platform of the Secretary of Labour. Furthermore, they identified the young people who wanted to become entrepreneurs, directed them to courses that were being given, and, finally, monitored their businesses. The intervention helped in the creation of four OMSs joined to the structures of the municipalities of Cane, Comayagua, La Esperanza and Marcala, and all of their operations were undertaken by their respective town halls – a key element for sustainability.

4. RESULTS AND IMPACT

Young men and women who were likely to migrate, or those who were just returning, boosted their ability to properly incorporate themselves into the labour market. A total of 2,838 young people (52 per cent women) improved their skills in order to access the labour market and now have more resources to create and manage their own businesses. 1,580 direct jobs were generated, 1,226 young people created their own business units, and 438 business plans were developed.

National and local institutional frameworks were strengthened to promote proper employment to the young people likely to migrate and returnees. The programme incorporated the theme of juvenile employment into the strategies and tools developed by the leading institutions, such as the Secretary for Work and Social Security, the Secretary for Foreign Affairs, and the Secretary for Social Development at a central level. The same happened in regional and municipal areas, and was reflected in the intervention zones’ regional and municipal development plans. As well as the creation and implementation of the OMSs, three inter-institutional committees for youth employment were organized. These were established in the framework for the three territorial boards organized and integrated in the regional councils for development which, from the start of the intervention, conducted the National Plan of Youth Employment.

In terms of the gender awareness strategy, a manual called ‘Gender, Employment and Prevention of Violence’ was developed, which served as the basis for a series of five workshops that 521 women and 660 men participated in. Furthermore, those in charge of coordinating the four OMSs were four women from the area which received training through the programme.

Additionally, the programme gave financial support to 1,417 young people who wanted to start up a business and who developed a viable business plan. This support was given in two different ways:

- A credit fund managed by credit co-operatives and rural funds. In the urban areas, four credit co-operatives managed the funds: COMIXMUL, COMUPPL, COACFIL and COMIRGUAL. Two of these co-operatives (COMIXMUL and COMUPPL) were created for and by women. Of course, the programme also gave loans to joint business associations. In addition, the young people received help and technical support to put their business plans into action. In total 246 young people had access to credit to set up their own businesses: 129 individual women, 106 individual men, as well as 11 associations of joint ventures. The total amount given out was approximately 5.5 million Lempira: 3 million given to women and 2.5 million to men.

- In rural areas, support was given through the Engage Young Rural People project, implemented by FUNDER, which, before the programme, only worked with adults and primarily men. After the intervention, the group that used its services was increased. The rural funds were in charge of assigning money. 45 rural funds were selected and assigned a rotary fund of 7 million lempira. A total of 544 young people (45 per cent) women accessed microcredit managed by FUNDER and received training and technical assistance to start their own business activities.

- “Seed Capital” fund managed by local administrations in coordination with the OMS. For the first time this fund enlisted the help of the municipal town halls in the areas of local economic development through entrepreneurship owned by young entrepreneurs.

The municipal offices of Marcala, Comayagua and La Esperanza, in coordination with their OMS, managed this fund, which was endowed with 3.5 million lempira. The funds, which did not have to be repaid, aimed to support already-established business activities that needed improvement to continue functioning. Evaluating the viability of the business was the OMS’ responsibility. Those in charge of coordinating these four OMSs were women from the area who received training through the programme. 320 young people (153 women and 167 men) participated. As a result, 371 new businesses were created, of which 326 were run by individuals and 45 in joint ventures.

5. CHALLENGES

- At first, the programme did not include a universal gender focus. However, despite this initial omission, the programme managed to rectify this and, in the end, led to a high percentage of young women participating through the training, technical help and credit offered. It is very important to incorporate gender equality as an essential part of the integral programme’s strategy. The lack of a gender focus initially undermined the programme’s potential to encourage equality and the empowerment of women. At the start, the workshops about gender, employment and prevention of violence were disconnected from other areas of the programme. Once the target audience had been widened and included men and women from the two financial assistance and training for entrepreneurship programmes, the integral nature of the empowerment process was reinforced. This also shows that it is possible to adjust the focus of a programme to introduce changes during its implementation, and to yield more solid results.

- Creating harmony between the programme’s agencies was a challenge in terms of the co-ordination of actions, methodologies and lead times. There were cases where the same thing was done twice, which could have been avoided with a preparatory phase to structure activities and tasks between agencies, and by performing administrative and implementation adjustments. From the perspective of co-ordination, the intervention could have been more successful if an operating manual or tool to synchronize the implementation of actions had been given out. This shared tool, which should include a clear definition of the role of the leading agency, would have allowed the UNDP to fill its role more emphatically.

Honduras is characterized by a predominance of young people - 67% of the population are under 29

6. LESSONS LEARNED

- The programme is a successful reference of the abilities and the impact of the United Nations when its agencies work in a coordinated and multidimensional manner. Each one brought its own knowledge and experience. Of course, in order for the intervention to be successful, it is very important that clear roles are assigned and agreements established about communal objectives, followed by mutual learning by the connected agencies and institutes.

- Initial gender analyses are essential for interventions with women to be successful. To guarantee that the strengthening activities of the value chain contribute to gender equality and the empowerment of women, it is essential to conduct a gender analysis at the start of the intervention, so that inequalities – in terms of opportunities, decision making, workload and income – can be adequately addressed during implementation. When gender inequality is the norm, there is a higher risk that the women will not gain full benefit from the interventions. This could lead to men restricting women from participating in training or commercial activities, and so women suffer from a larger workload, or even a lack of control over additional income generated by their entrepreneurial initiatives. The programme did not do an initial gender analysis, and it is one of the aspects that, in future interventions, should be improved. Aside from lacking an initial gender strategy, female participation in the programme’s activities was practically the same as male participation. This proves that, despite the numerous barriers that women encounter, they have a strong desire and motivation to access paid employment and become economically autonomous. To respond to these demands, all youth employment programmes should begin by examining preconceived ideas about interest and availability for employing young women and, in addition, put methods into place for eliminating the barriers which limit their access in terms of familial responsibilities, less economic and social capital, and gender stereotypes, among others.

- Young people can receive credit. The programme demonstrated that, with supervision and appropriate support, young people can be subject to credit. The participating credit co-operatives and the rural funds in the programme modified their initial orientation, which was centred almost exclusively on adults, to open their credit plans to young people.

Unemployment in Honduras particularly affects women, who also suffer from a clear wage inequality

- The rural artisanal sector is a motor for local development. The politicians tend to give priority to heavy industry development and overlook the farming sector and the small rural businesses. Of course, the programme demonstrated that supporting the traditional farming sector, guaranteeing important cultural values, can contribute to generating employment and stimulating the local economy in rural areas which have been lagging behind economically and socially. Furthermore, the artisanal sector mainly employs women. Supporting the business initiatives of rural women was particularly valuable and efficient to achieve female empowerment and, in this way, improve familial income and wellbeing, and stimulate local economic development.

- Involving adults is key for the success of the intervention. Involving leading adults in the organization process and putting training into place promoted strengthening of generational links and enriched the process, as they brought their experience. Also, it generated more confidence between the fathers and facilitated the participation of young people. Future experiences of entrepreneurship with young people should include the presence of adults to facilitate their participation and guarantee the integrity of the process.

- Working in a group contributes to improving productivity and profitability. By being organized in a co-operative manner, the young people managed to improve their businesses and reduce their production and transport costs. The transmission of new knowledge and abilities to rural women by women from their own community was particularly useful in the towns comprising ethnic minorities, as speaking the same language makes communication much easier.

7. SUSTAINABILITY AND POTENTIAL FOR REPLICATION

The methodology of the programme can serve as a reference for other countries on their approach to unemployment and youth migration. The design of the intervention incorporated from the start aspects relative to its sustainability, community participation and institutional empowerment of the key players being especially relevant.

The programme constructed discussion spaces and analyses which allowed them to integrate the theme of youth employment in the regional and municipal programmes, and also in the institutions who participated in the implementation’s operative schemes. The work and dialogue space between civil society – such as the territorial boards and the Multi-Service Offices – were key for the sustainability of the actions, since they were subsequently integrated into the regional planning structure. During the intervention, the town halls were totally responsible for the four OMSs; they all functioned with an appropriate budget from their own municipalities, and three of them were integrated into physical and administrative structures. At the end of the intervention, the OMSs became a part of the National Service for Employment of the Secretary of Work and Social Security.

This experience strengthened the local institutions, developing their technical capacities and financial resources. This will allow them to improve their work in promoting youth employment opportunities as well as gender equality in the labour market. In this way, after the intervention, the members of staff were able to identify and break down specific gender-related barriers in their work.

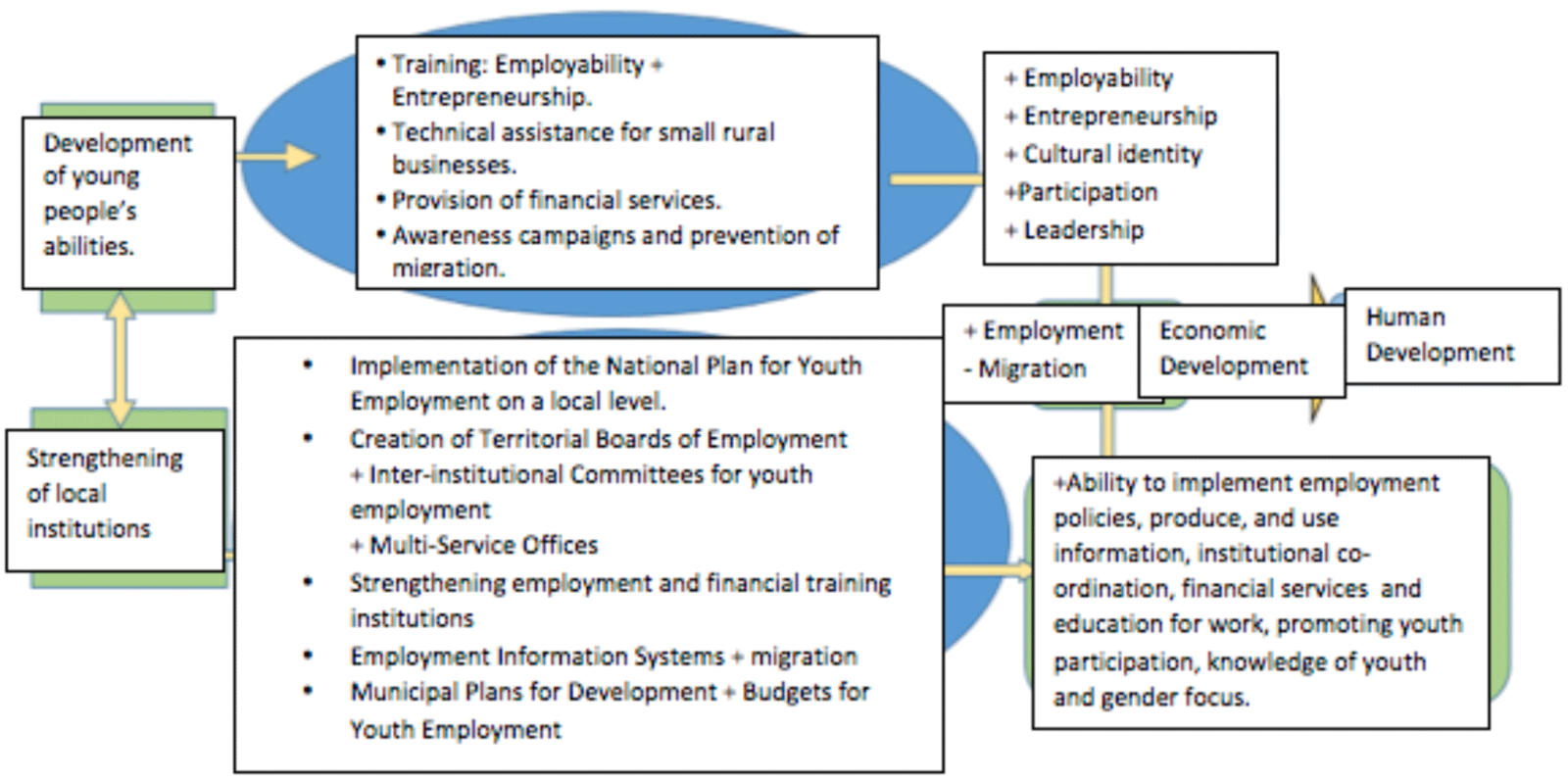

The integrated local development models in youth and employment boosted by the programme can be a reference for employment projects that happen in Honduras, but also in other countries. This is a flow-chart with the Theory of Change put into place by the intervention: