On May 28, 2012, Law 243 against the Harassment of and Political Violence against Women was passed, which did not limit its implementation to elected officials, but broadened its scope to appointed women or to the exercise of political or civil service

Case study

Institutional strengthening against gender-based political violence in Bolivia

SDGs ADDRESSED

This case study is based on lessons from the joint programme, Integrated prevention and constructive transformation of social conflicts: promoting peaceful change

Read more

Chapters

Project Partners

1. SUMMARY

The intervention aimed to promote a prevention process of social conflicts in Bolivia, creating strategies to address harassment and violence against women in the context of political participation.

In particular, progress was made in assisting victims of political violence, working in parallel for their empowerment and the development of a more favourable decision-making legislative framework for women to participate in, through the adoption of a national law to combat political violence. This law is the first of its kind worldwide.

The programme was set on 3 foundations:

- Support for strengthening the rule of law.

- Accompanying the legislative development in the new constitutional framework.

- Developing abilities for thematic conflict management.

This case study analyses practices, lessons learned, results and challenges with the intention to strengthen and expand available knowledge on the empowerment of women in the political sphere.

Over the past few years, Bolivia has improved its legislation to promote women’s participation in politics

2. THE SITUATION

Bolivia is undergoing a period of transition from a strictly representative democratic model to another more decentralized model, which promotes greater direct participation from the community on public issues, and is clearly aimed towards greater social equity.

The transition challenges arise in three areas: 1) strengthening a more inclusive rule of law; 2) the pursuit for full citizenship that is capable of defending human rights through active participation in decision-making processes; and 3) the meeting between the institutional and the exercise of citizenship, where the challenge is building spaces that bring citizens closer to their institutions and vice versa.

In this sense, to have an impact on the lack of women in decision-making and the violence that they suffer when they reach public office is crucial in achieving an equitable rule of law. In recent years, the Bolivian legislation to promote political participation of women in different areas of public decision has improved. However, neither the so-called quota law of 1997, which only referred to elected officials, nor the introduction to a new quota system in 2004, which required the presence of one woman for every three candidates, proved effective solutions to the lack of women in Bolivian politics. One of the reasons was the absence of sanctions for noncompliance, even though the responsibility for ensuring this was entrusted to the National Electoral Court and the Departmental Courts. In many cases, this loophole enabled political parties and citizens' associations to mock legislation by presenting male candidates that passed as women on the lists.

Finally in 2010, after a long process, a decisive action in favour of political participation of women was passed applying the principles of equity and parity in the Political State Constitution and the current electoral law. Since then, although in Bolivia there had been significant progress in women's participation in quantitative terms, these developments brought new challenges. First, the need to carry out sustained actions to verify equal participation of women and men in electoral processes and to set clear sanctions for noncompliance was evident. Moreover, problems related to discrimination, manipulation, and political violence against a growing number of women in the public sphere became recurrent, which made it necessary to adopt policies and concrete actions to promote the political participation of women and the elimination of violence to which women are subjected.

3. STRATEGY

Measures adopted by the programme sit within the strategic framework of the Political Representation of the Five-Year Plan of the Bolivian Association of Councilwomen (ACOBOL). They have developed four lines of action, each of which presents a specific strategy:

- Designing, disseminating, and updating the bill against the Harassment of and Political Violence against Women. From the beginning, a strategy was developed to forge alliances with other institutions interested in the subject carrying out a combined advocacy effort aimed at passing the law.

- Protocol design for attention of cases before the Electoral Court. A combined strategy agreement between the Supreme Electoral Court and ACOBOL was agreed upon, with the support of the programme, aimed at developing awareness processes, training, and validation of the protocol.

- Development of actions for attention of harassment and political violence cases. A decentralized intervention strategy was used that took advantage of the departmental associations of councilwomen network, for which technical advice for affected women was offered.

- The women councillors’ empowerment actions. On the one hand, awareness and training processes on this subject with different stakeholders were carried out; and, on the other hand, actions of empowerment and self-esteem building of 600 councilwomen (mainly in rural areas) were developed.

4. RESULTS AND IMPACT

Approval of Law 243, of May 28, 2012, against the Harassment of and Political Violence against Women:

This process began in the year 2000, at a Commission of Popular Participation of the Congress of the Republic meeting, where councilwomen publicly denounced the harassment and political violence exerted against them in different municipalities. In 2001, they carried out the first motion directed to the design of the first bill against harassment and gender-based political violence. In the following years, and on the basis of this first bill, coordinated work between various institutions to systematize and disseminate the bill continued to develop.

One of the most important results of the work done in those years was, in 2004, the creation of the Political Rights for Women Action Committee composed of representatives of different institutions working on gender issues. Since the formation of this committee, increased awareness and empowerment of women from different public institutions on the importance of harassment and political violence issues has been achieved.

Finally, Law 243, of May 28, 2012, against the Harassment of and Political Violence against women was passed, which did not limit its implementation to women in elective office, but extended its reach to women appointed or practiced political or civil services, representing a difference from the first bills presented.

This law establishes a classification of acts of harassment and political violence, distinguishing between minor, serious, and very serious offences and sets sanctions for each category, which allows clear identification of these acts and their corresponding punishments. In cases of harassment or political violence, the victim or her family, or any natural or legal person may file the complaint, verbally or in writing to the appropriate authorities. There are three channels of complaint: administrative, criminal, and constitutional. In the case of criminal proceedings, the incorporation of new criminal categories in the Bolivian penal code was an important step forward for this regulation. This channel prohibits reconciliation, in order to avoid greater pressure on victims of harassment and political violence. At the same time, a study on the problems and obstacles for women to participate in the electoral process was conducted.

Protocol for attention to cases:

The experience of recent years in advocacy work for the passing of the law expressed the need to generate additional tools that facilitate and guarantee the enforcement of the new regulations. For this reason, the “Attention and Treatment Protocol for Victims of Harassment and Political Violence in the Electoral Jurisdiction” was drawn up, to establish the basis of action by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal and the departmental electoral courts in regards to assistance and treatment for victims of harassment and political violence, as well as timely and flexible proceedings of administrative matters to ensure no impunity for these acts1.

Hard limits still exist to achieve institutional environments that are pro-women’s rights

A joint strategy was agreed between the Supreme Electoral Tribunal and ACOBOL, with the support of the programme, aimed at developing processes of awareness, training and protocol ratification, by organizing workshops2, which were coordinated by ACOBOL, the Departmental Associations of Councilwomen, and the Intercultural Democratic Strengthening Service. The workshops were directed to municipal representatives and officials of the departmental electoral courts. To complete the process, the National Electoral Gender and Intercultural Workshop with the aim to complete and reinforce the process of training and socialization of the main issues addressed was held. The results of the work carried out in the departmental workshops were presented, particularly those related contributions of the “Attention Protocol for Victims of Political Violence”.

Obtaining evidence and responses to cases of harassment and political violence:

The “Form for Reporting Harassment and Political Violence” was designed to record and track cases dealt with and the background to these. This form includes a section that must be completed by the specialist to evaluate the type of action, the seriousness of the case, and the recommended actions to be taken.

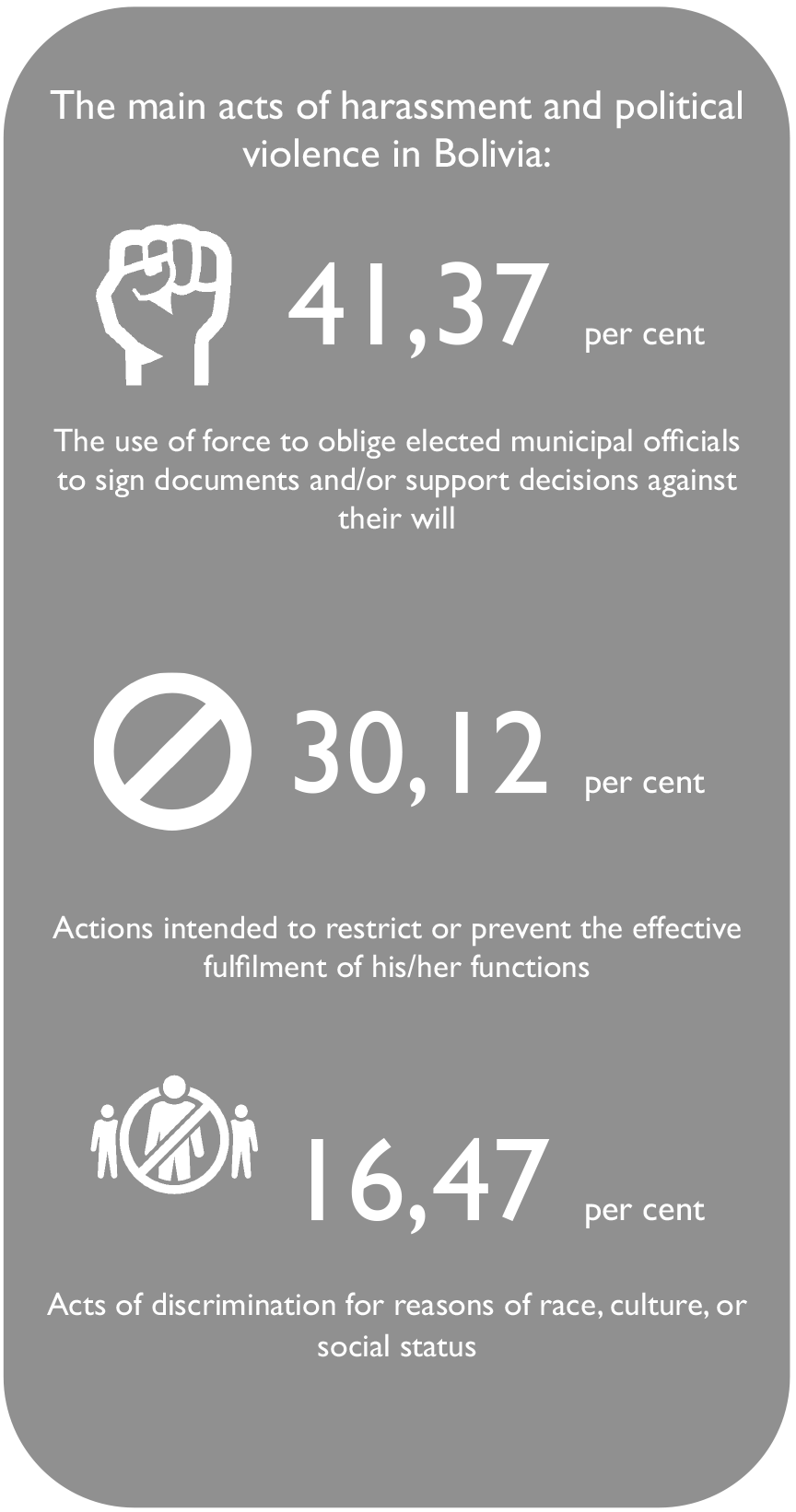

In 2011, the “Manual for the Systematization and Classification of Harassment and Gender-based Violence” was designed to record cases dealt with in the Departmental Associations of Councilwomen. This is an important tool to guarantee the consistency of recording information. The systematic recording of cases helped to set the terms of the Law against the Harassment of and Political Violence against Women. The main acts of harassment and political violence are associated with the use of force to oblige elected municipal officials to sign documents and/or support decisions against their will (41.37 per cent); actions intended to restrict or prevent the effective fulfilment of his/her functions (30.12 per cent) and acts of discrimination for reasons of race, culture, or social status (16.47 per cent).

To complete these aspects, information was disseminated and processes of awareness on harassment and political violence were developed. The importance of disseminating information was revealed during the Gender and Intercultural Electoral Workshop organized by ACOBOL in collaboration with the Supreme Electoral Tribunal. In this workshop, elected municipal authorities that attended recognized that, in many cases, female victims of harassment or political violence were not aware nor did they know that their political rights were being violated; hence the reason that they did not report the incident nor undertake any type of action. Another important development was the creation of the Observatory of Women’s Political Participation in Local Level Bolivia. The observatory was designed as a space for raising the visibility of the political participation of indigenous women, natives, farmers, Afro-descendants and those living in cities more visible at the municipal level and of their potential and contributions in municipal development, their participation at national and international levels, as well as the harassment and gender-based violence suffered by councilwomen in municipalities of Bolivia.

5. CHALLENGES

- The intervention was conditioned by the socio-political environment in which it was inserted; also, being a process of support to a number of policies and institutions, which meant limitations from the point of view of the assessment of results. Despite the aforementioned, the positive elements are numerous; especially because the scope of many elements can be assessed very positively (drafting and passing of laws, development of institutional strategies, publications and dissemination of regulations, etc.)

- Hard limits still exist to achieve institutional environments that are pro-women’s rights. Despite efforts made in the assistance and treatment of harassment and political violence cases, there are still very few that resolve in women’s favour, as seven out of ten go unpunished. It is important that assistance and support agencies supervise and accompany the handling of cases up until their conclusion. If this isn’t done, there is a risk that the victim will abandon her case due to fatigue or because the reason for the complaint has worsened, leaving her in an even more vulnerable situation. This could discourage other victims to report.

- It’s necessary to work harder to strengthen the legal departments of the institutions. Technical and legal advice offered by the departmental association of councilwomen staff presented limitations of a technical nature. Not all associations have legal professionals on staff, as well as political in nature, as its officials run the risk of political pressures to abandon the attention of cases. This double threat may contribute to a decline in positive legal outcomes for victims. One of the assistance modalities analysed is to outsource this service. However, for this method to be successful, it is necessary to establish a dialogue in coordination with professional bodies and / or universities to train lawyers and give them a certificate that guarantees their additional capacity to deal with these cases and to manage the database of professionals available to victims of harassment and / or political violence.

6. LESSONS LEARNED

- Records of political violence cases have facilitated the systematization of these acts and their incorporation into the new law. A recommended practice for those institutions that address harassment and political violence cases is to keep accurate records, for which purpose instruments should be designed that allow data to be gathered consistently. These records can become an important source of information for research, public policy design, etc.

- Involving strategic plaintiffs and empowering them on problems of harassment and political violence made it possible to pass the law. For many years advocacy actions were carried out with the National Parliament, without obtaining favourable results. In the past two years, the strategy of involving and achieving the ownership of this issue by some women national assembly members allowed the process of this bill to be prioritized and expedited until final approval.

- Dialogue processes between groups, building relationships, joint efforts and concrete interventions on specific problems are considered optimal means to allow progress on key issues on peace building. Generating opportunities for dialogue among those responsible for dealing with cases and victims of political violence allowed officials to acquire a real understanding of the importance of this issue. Initially, the persons responsible for dealing with cases did not appreciate the impact on victims and democracy. Spaces of discussion designed for building assistance protocols for victims allowed authorities and technicians to expand their knowledge and commit themselves to improving the way cases are dealt with.

- Processes of diffusion and training of public institutions responsible for dealing with cases of political violence are a key measure for prevention. However, this work should be extended to various public institutions, representatives and members of political parties, and civic groups.

- Developing guides as courses of action that serve as reference material, as much for municipal councilwomen who are victims of political violence as for those responsible for counselling and assisting in these cases, is vital for building capacity in public institutions.

Nicolasa Rora, joint programme beneficiary

7. SUSTAINABILITY AND POTENTIAL FOR REPLICATION

The intervention methodology developed by the programme can serve as a reference for other countries in the fight against gender-based political violence, as well as in the design of legal instruments, tools and public policies focusing on institutional strengthening and empowerment of women in decision-making.

This intervention is particularly relevant for community participation and institutional empowerment of the stakeholders involved, mainly women's organizations. Accomplishing synergy between different institutions working on related issues determined the success of the process, but also ensured its sustainability. The ability shown by participating organizations to adapt to political and institutional changes allowed them to survive and continue the actions over time. Since its inception, the Political Rights for Women Action Committee has been formed by public institutions, which in some cases have disappeared or have been transformed. However, the continuity of institutions like ACOBOL, among others, that have gone ahead over the course of years, have allowed the organization to conduct its work, and are a key element to sustaining the intervention.

Spaces for discussion allowed authorities and technicians to commit themselves to improving the response to political violence against women