“The programme enabled me to socialize with the community. Through the administrative boards of rural aqueducts, it is us who take care of the systems that are offered. The main users of water are women. These women are the guarantee to maintaining the aqueduct. Without water, we would be nothing. We do not want to keep drinking river water”. Mitzy Elena Castillo, President of the Administrative Board of Rural Aqueducts (Junta de Administración de Acueductos Rurales – JAAR) in Bisira

Case study

Indigenous women participating in water management in Panama

SDGs ADDRESSED

This case study is based on lessons from the joint programme, Panama: Strengthening equity in access to safe drinking water and sanitation by empowering citizens and excluded indigenous...

Read more

Chapters

1. SUMMARY

The intervention aimed to guarantee the provision and access to water and sanitation services for the most excluded populations in Ngäbe Buglé, giving men, women, girls and boys in the communities the opportunity to improve their living conditions and quality of life.

On the one hand, it aimed to develop effective and democratic governance surrounding water, through training and skills development as a means of achieving more civil society participation in water management, with a special focus on indigenous women. On the other hand, it also provided access to efficient and safe water systems by improving infrastructure.

This case study aims to present the lessons learned, results and practical examples to improve knowledge on water and governance with the addition of gender focus.

The intervention aimed to guarantee access to water and sanitation to the most vulnerable populations in the Ngäbe Bugle region

2. THE SITUATION

According to data from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Human Development Index of Panama in 2010 was high, putting it in 9th place in the Americas and first place in Central America. However, when disaggregating this indicator as a function of economic inequality and by gender, it falls by 15 positions and 95 respectively. These differences reflect the existence of significant social inequalities between the populations located in peri-urban, rural and indigenous areas. This is shown through data from the Ministry of Economy and Finance (2011), which indicates that poverty affects 16.4 per cent of the population in urban areas, while 96 per cent of the indigenous population live in poverty, and 41.8 per cent in conditions of extreme poverty. On the other hand, the dispersion of indigenous communities and their location in remote areas which are difficult to access increase the cost of traditional sanitation solutions, affecting the economic justification for investments and private participation.

The Ngäbe Bugle region, which accounts for 78.4 per cent of the indigenous population of the

country, faces significant poverty and inequality. The average household income is about US$ 60 a month, so it is not uncommon for water and basic sanitation services in some communities to be precarious or non-existent. The 2010 household census indicated that of 26,256 households in the region, 61 per cent had no access to drinking water and 59 per cent had no sanitary way to get rid of their excrement, with the common practice being using rivers both for water for human consumption and for other domestic uses - including the disposal of excrement. In addition, in the Bisira and Kankintu areas, where the project was being developed, there is substantial discrimination against women. This, together with the lack of income and access to basic health, water and especially education services, tend to make women very vulnerable.

The progressive fulfilment of access to safe and affordable water resources for all is crucial for eradicating poverty and for the protection of health, but it also particularly contributes to the empowerment of women. When there is no easily accessible water, it is mostly women who have to get it, often spending exorbitant amounts of time and energy. This situation brings problems ranging from physical disorders to the near impossibility of women being involved in other activities such as education, income generation, politics, or rest and recreation. Also, the lack of accessible services leads to much tension within the household, thus increasing the vulnerability of women to domestic violence.

Furthermore, while women are mostly responsible for water for domestic and community use, it is men who are attributed most rights associated with water and decision making in institutions. In this context, the implementation of the programme aimed to guarantee the population’s access to water, with special attention paid to the participation of women.

Safe and affordable water resources for all are crucial for poverty eradication and health protection

3. STRATEGY

Initially, the programme developed a gender analysis that identified potential areas for specific interventions. The prevailing traditional cultural patterns in terms of access to economic resources and the associated benefits marked out the “roadmap” to gender equality and women’s empowerment. It was necessary to strengthen and develop some basic social skills that strongly conditioned the participation and role of women in the community; this involved promoting as much the shared work of “brade” (men, in the Ngäbe language) as that of “meri” (women). Once the gender analysis was done, the programme adopted a dual strategy:

4. RESULTS AND IMPACT

The Programme provided the community with education and specific training in different areas such as: water management and good practices, hygiene and sanitary education, awareness of the environment, and the rights of women and children. It trained 23 school brigades, creating a network made of 117 educators and 160 young people. There were also workshops for disease prevention and training of microenterprises among rural and indigenous populations in building water infrastructures. For all of the above, didactic and audio-visual materials were developed and adapted to the Ngäbe culture.

In doing so, the social fabric of the communities involved was strengthened. One of the notable impacts was the empowerment of indigenous women, who participated actively in all phases of the programme, and who afterwards took on executive responsibilities within institutions related to water management. It offered women the opportunity to learn, share experiences, and demonstrate their ability to perform tasks which were previously only accessible to a man. For example, controlling of inventories of construction materials, or construction itself.

At the same time, it empowered communities to run water systems and to build infrastructure for water, sanitation and the health system - actions which were accompanied by the development of water quality assessment methods with plans to monitor quality. The main achievements are as follows:

- Nine communities have access to drinking water 24 hours a day (5,834 people). Solutions were established to provide water to 2,073 households along with sanitary systems to manage excrement.

- Two communities, Bisira and Cerro Ñeque, built 79 septic systems.

- Nine Water Security Plan (WSP) teams were created to monitor the aqueduct system built for the programme. Two design and construction microenterprises were also organized for the management and maintenance of drinking water and sanitation.

- A management plan was created for the Microcuenca de Norteño (northern microbasin), which upholds the creation of the Water Reserve by municipal authorities. Management plans in the Bisira, Kankintú and Sirain microbasins were also created, and the Cerro Ñeque water reserve was demarcated.Since then, it has been protected by the community.

- Nine rural water boards (JAARs) were created. Organizational strengthening of the JAARs implies major benefits for communities. The empowerment of the women involved promoted their participation in communities and built trust and autonomy. This was the case to the extent that, after the intervention, women were elected as presidents of the JAARs.

- The organization, swearing in and capacity building of the Ngäbe Women’s Network (Red de Mujeres Ngäbes).

When water is not easily accessible, it is mainly women who are responsible for obtaining it

5. CHALLENGES

- The scope of the programme in terms of coverage varied across communities. The total population covered was approximately 54 per cent of that initially planned. This was due to errors in calculating the cost per family, in addition to the price increase of materials, gasoline and transportation which had a notable effect on the development of projects in remote regions.

- At the beginning of the programme it was difficult to involve women, but each of the United Nations agencies involved took on a share of this work. UNICEF managed to involve them in programme activities. The ILO trained women entrepreneurs, and the WHO identified women leaders capable of transmitting knowledge and ensuring sustainability. This experience showed that a design which is multidimensional, but at the same time clear and simple in terms of the number of partners involved, speeds up administrative processes and ensures good communication, coordination, and implementation of actions.

- The governance model was developed through social dialogue and constant feedback, respecting the relationship between interculturalism and water management. The intervention created a horizontal and collaborative relationship between the participants, where all parties had a voice and a vote. This required a major time and resources investment to create the necessary conditions and to involve all parties in each one of the phases.

6. LESSONS LEARNED

- For the intervention to succeed it is very important that the roles of the different United Nations agencies is clear, to establish agreements on common goals and to achieve mutual learning on the part of the agencies and other institutions involved.

- Involving people from the communities from the first steps of programmes is vital for the sustainability of actions. In so doing, beneficiaries adopt and defend the interventions as their own.

- To guarantee the participation of women in programmes it is necessary to educate communities in the distribution of domestic responsibilities and child rearing. In this intervention, the greater involvement of men in household tasks facilitated the participation of women in all activities of the programme. The women gained the respect of the community by actively participating in the infrastructure projects for rural water and health systems, because their abilities and knowledge were valued.

- Building infrastructures in the Kankintu and Bisira communities generated employment opportunities. The programmes should not stop their actions at this time, but must promote that women and men can equally benefit from the employment opportunities generated. Also, hiring local labour not only lowers the cost of programmes, but it also contributes to the empowerment of communities and the sustainability of the work.

- It is important to incorporate an explicit strategy on gender equality (and not only a transversal one) in local development programmes in indigenous areas, especially in terms of being involved in water management. Understanding the roles, relationships and inequalities between genders may help to explain decisions made by men and women, as well as their different options. Inequalities influence both perception and participation in the use and management of water.

- The remote location of these communities means that not many professionals are willing to take the necessary risks to share experience with the groups and to train them. Therefore, when it comes to indigenous communities, it is absolutely necessary to strengthen local capacity to carry out these activities and to ensure that their success can be sustained over time.

- To properly compare the initial and final situations it is very important to define success factors and to measure them before beginning the programme and afterwards. These may include health factors in addition to qualitative social aspects, such as community participation, women’s empowerment, and organizational strengthening.

Infrastructure construction generated job opportunities

7. SUSTAINABILITY AND POTENTIAL FOR REPLICATION

Practices and models of local development in water and health management promoted by the programme may serve as a point of reference for other water projects being executed in Panama, as well as in other countries. This intervention is especially relevant for community participation and empowerment - in particular of indigenous organizations and leaders.

All of these elements contributed to enriching the knowledge and world view of Ngäbe men and women and their relationship with water. This helped significantly in decision making, a process in which communities are not considered just as beneficiaries, but also as collaborators and managers of their own development. Also, the participation of women in the rural water boards laid the foundations to improve the situation, and was also key for the sustainability of actions. Women have many relationships within the community and involve their family members in their activities. So, their participation and leadership contributed intensely to the development of the community and continuity of initiatives.

Similar future efforts will need to take into account that, for water governance processes to succeed and be sustainable, investment in infrastructure is key. Both initiatives were linked to the understanding that physical investment without social and institutional empowerment is neither sustainable, nor benefits from appropriation. In turn, processes of participation, empowerment and governance without tangible solutions in the short or medium term can be frustrating for beneficiaries and thus make them unsustainable.

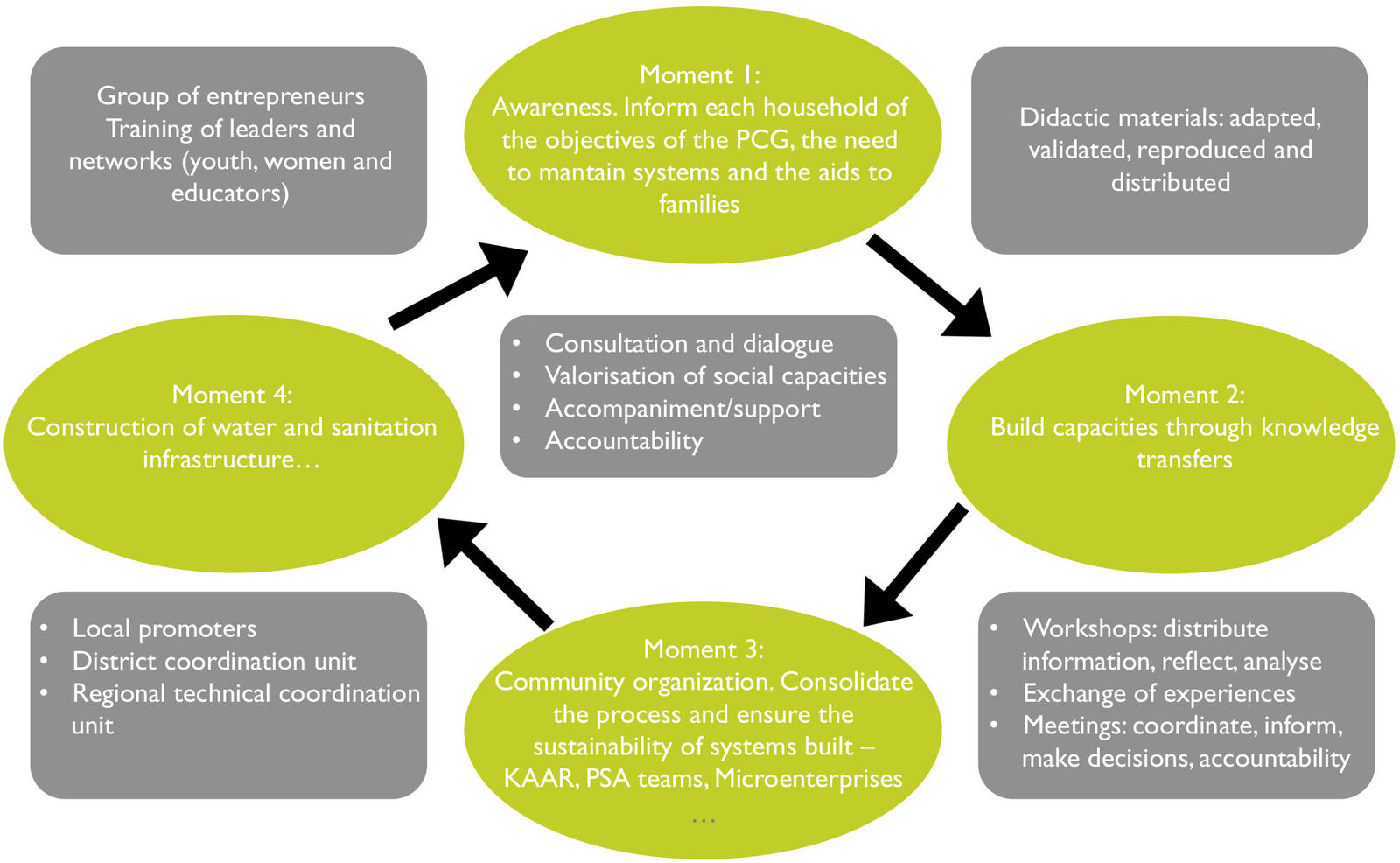

Social development does not respond to linear or step-by-step schemes or designs. The execution of programmes needs most efforts to succeed in establishing a logical approach to identifying problems and actions to overcome them with the participation of the majority of those involved. However, we can identify four key moments in the methodology of the programme’s implementation which, together, contributed to breaking down traditional intervention schemes for building water and sanitation infrastructure.

In summary, the factors of success and sustainability consist of: 1) investing time and resources to meet local partners and to create the base for the participation of beneficiaries, leaders of organizations and officials; 2) define beneficiaries and methods as early as possible; and 3) design an administrative structure responsible for organizing and coordinating the intervention.

These four key moments are illustrated in the next schematic: